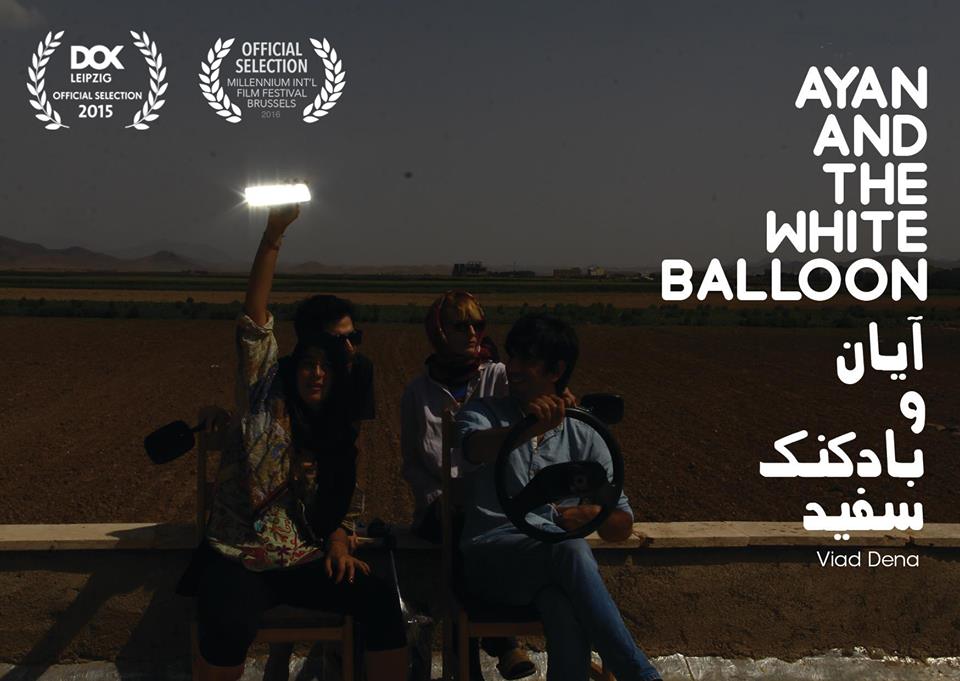

The annual International Documentary Film Festival, (or ‘Millenium’) held in Brussels is not only a platform for the international film community to view fantastic entries, but it also serves as an opportunity for emerging talent to showcase their work. Born in Iran, Brussels-based artist Vida Dena was among the 2016 festival participants with her documentary film Ayan and the White Balloon. Inspired by themes involving censorship and dual identities, we take a behind-the-scenes look at Dena’s latest film and how this talented multimedia artist explores connecting European and Middle Eastern cultures.

Initial Success

The immediate international success of Ayan and the White Balloon at the World Premiere of the 58th International Leipzig Festival For Documentary and Animated Film has somehow overshadowed the rest of Dena’s works (short films, drawings, installations), almost as if the short film is viewed as a fortunate occurrence. Rather, the success of the film is the result of a symbiosis of deep and far reaching historical and cultural roots of the director and her artistic knowledge and intuition.

Dena is dedicated to showcasing what is special about contemporary art from Iran, commenting that, ‘the festival is a unique opportunity especially for talents living far away from their homes to present their works, a chance for immigrants with ambitions and hopes, curious and sometimes naïve like children in the middle of a foreign metropolis to think out loud and express their personal and political concerns.’

Dena’s Childhood Among Artists

Self‐censorship, double identity and dislocation are the core ideas of Dena’s work. The Brussels-based director has been influenced by art since her childhood. Her mother introduced her to arts at a very young age. ‘If my mom was not an artist, I might not be one! She had a gallery in Iran and I was always in the artistic atmosphere,’ says Vida.

Dena pursued her passion for visual arts at the University of Tehran where she received a Bachelor’s degree in Architecture. In the summer of 2009 she left for Sweden to continue her Master in Fine Arts at the Umeå Academy of Fine Arts, to finally obtain a Master’s degree in Audiovisual Art. Continuing her education, Dena then moved to Belgium in order to get another Master’s Degree in Film from KASK School of Arts Ghent in 2015.

‘I am a very nostalgic person and the fact that I immigrated from my home country made me even more nostalgic!’ – confesses the artist. ‘What I do as an artist is more about expressing myself and my feelings, but at the same time since the political and the social situation in Iran keeps concerning me, I always try to criticize the situation through my personal experience and my life in Iran.’

‘The childhood of mine is a strong part of my biography. I really enjoyed my childhood because my parents and my family gave me love and happiness, not the society, unfortunately. What’s most important is my strong feeling about life that comes directly out of my childhood!’

The Millenium Documentary Film Festival 2016

In her film Ayan and the White Balloon, the protagonist named The White Balloon goes back to her home country of Iran after five years of living in Europe to ask her old friends to play in her film. To her surprise, her friends are reluctant to help her, blaming her for going along with European stereotypes. Frustrated by this, the White Balloon gets into a fight with her best friend Ayan.

‘I went back to Iran to make a film about the collective moments in Iran,’ shares Dena. ‘In Europe, I found the life of people very individualistic and I was missing the collective feelings and activities. Therefore, I asked my friends to help me with the film but then I realized that they were not really happy with the fact that I was making another cliché film about the life of Iranians: the bribery scene, the fact that the alcohol is forbidden in Iran, the limits of young people in Iran presented by the religion and the society. So, I decided to make a film about the process of insisting and convincing them to play the scenes of the bribery and the moments when they were trying to convince me not to make this film. But on the other hand, I wanted to criticize lots of things: immigration, why do we immigrate, how do we change, what is friendship, why do I not go back…’

As somebody once beautifully put it, once an immigrant, always an immigrant. In the same vein, Dena answers the question of how her birth country shaped her personality and her career as an artist. ‘I am obsessed with my motherland, not in a nationalistic way but in a very nostalgic way. Moreover, the fact that I am Iranian made me an artist. I had things to say and as long as I did not have enough freedom to talk what I want and to do what I want, I decided to make art! Art as a weapon, as a medium of expressing myself, exactly like when we are sad and we need to cry. I had things to say and I needed to create…’

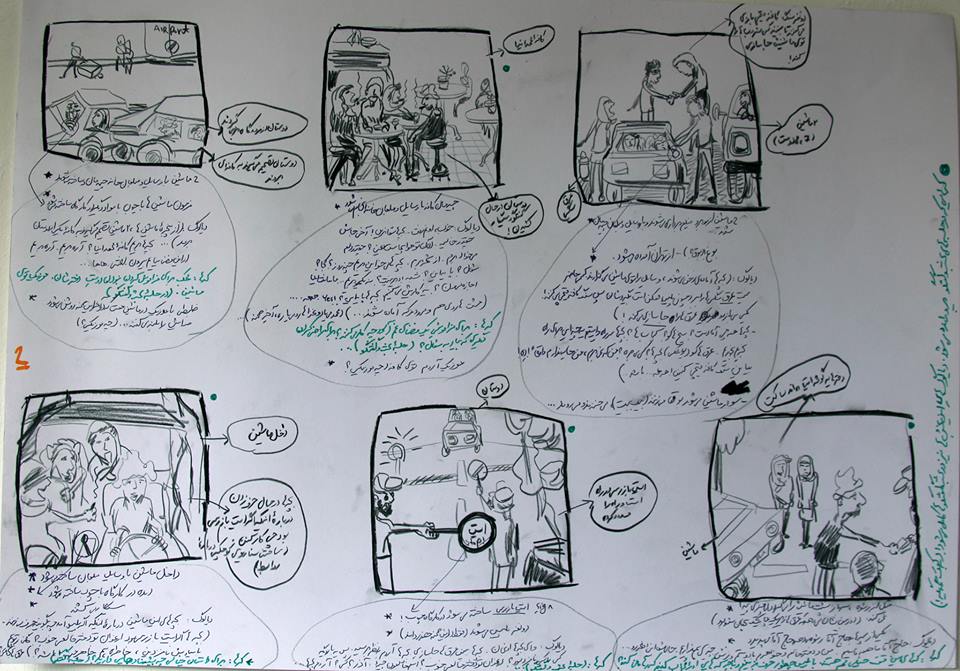

Transmitting Emotions Through Handmade Storyboards

Even though film directors have made significant use of modern technology in recent times, many realize that high tech does not always take the lead in the production process. Sometimes what matters is not the know-how, but the emotion that the artist can transmit to a simple thing, like a storyboard. ‘I actually draw a lot, says Dena. ‘I draw my dreams and I get inspiration from them, I use dreams to do the staging for my films, very surrealistic mise-en-scenes. Without drawing and writing I cannot do art. I do not believe in all digital approaches. I believe that handwork always remains original and necessary.’

Career Aspirations

Dena’s next film is about immigration. ‘It is not strange! I think lots of people are obsessed with this subject right now, but my film will be very surrealistic. You will hear about it more soon’, says the director. Answering the question of what would you most like to make that you haven’t made so far, Dena replied that she dreams to make a film about her childhood, her family, to remember the great moments together with the relatives and then to remake those memories into a film.

By Marina Kazakova